article image source: australianwildlife.org (link)

Australia’s lush tropical rainforests, long celebrated as powerful carbon sinks, are now releasing more carbon than they absorb — a dramatic shift that could reshape how the world approaches climate change mitigation.

advertisement

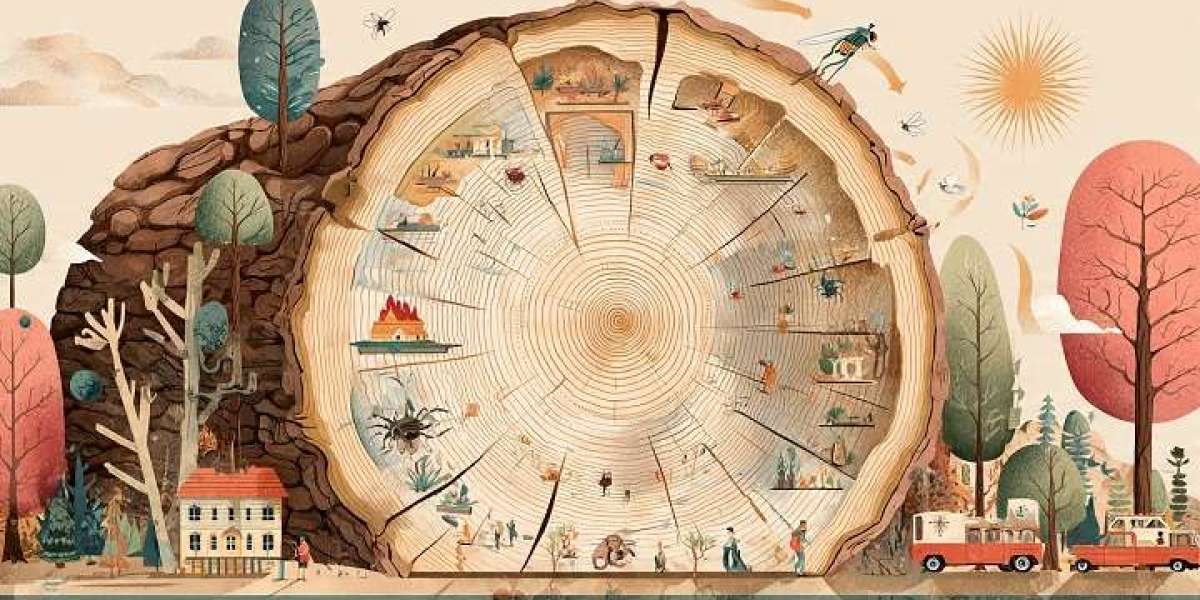

A Historic Change Unfolding in the Trees

For decades, the wet tropical rainforests of Queensland have acted as natural climate regulators, pulling carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere and storing it in their massive trunks, branches, and soils. But a landmark study, based on nearly 50 years of data from over 11,000 trees, shows these forests have crossed a critical threshold.

Around the year 2000, scientists observed a shift: these rainforests started emitting more carbon than they captured. What once acted as a buffer against rising emissions is now contributing to the problem.

“We’re witnessing a transition from carbon sink to carbon source — and Australia is the first place globally where this has been clearly documented in intact rainforests,” said Dr. Hannah Carle, lead researcher from Western Sydney University.

Image credit: Wayne Lawler/AWC - image source: australianwildlife.org

What’s Causing the Shift?

The main driver behind this change is an increase in tree deaths — a consequence of intensifying climate stressors:

Higher temperatures and drier air are putting trees under extreme physiological strain.

Severe droughts, such as the El Niño event in 1998, have disrupted natural growth cycles.

Tropical cyclones, including Cyclone Larry in 2006, have damaged forest structure and made trees more vulnerable to pests, disease, and future droughts.

Even though higher atmospheric CO₂ levels should theoretically promote tree growth, that benefit appears to be overwhelmed by the toll of rising climate extremes. These forests simply cannot keep up — more trees are dying than growing.

Image credit: Wayne Lawler/AWC - image source: australianwildlife.org

The Numbers Behind the Decline

Between 1971 and 2000, Queensland’s wet rainforests were absorbing about 620 kilograms of carbon per hectare per year. But from 2010 to 2019, they began releasing around 930 kilograms per hectare annually — a net reversal.

This shift wasn't just observed in a small patch. The data spans 20 rainforest sites, from lowland areas to high mountain elevations, offering one of the most comprehensive rainforest carbon records in the world.

Why It Matters for Australia — and the World

This discovery has major implications:

Climate modeling assumptions may be flawed. Many of Australia's (and the world’s) emissions targets rely on forests continuing to absorb carbon. If these natural systems are no longer reliable sinks, climate policies must adapt quickly.

Emissions budgets may be underestimated. Forests were thought to absorb about 25% of human CO₂ emissions. If that capacity is shrinking, we may be closer to breaching critical climate thresholds than previously thought.

Global forests could follow suit. While the Amazon and other tropical forests are still net carbon sinks, they may face similar pressures in the future. Queensland’s rainforests could be a warning sign of what’s to come elsewhere.

Forests Are Still Part of the Solution — But They Need Help

Scientists caution against blaming forests for this problem. As Professor David Karoly noted, the carbon released from dying trees is not "pollution" in the traditional sense — it's part of a disrupted natural cycle made worse by human-driven climate change.

Moreover, forests still store vast amounts of carbon underground in their soils and roots. Their biodiversity is irreplaceable. But for them to keep helping us fight climate change, we need to address the root cause: rising emissions from fossil fuels.

“Forests can only do so much,” said Dr. Carle. “They’re in a delicate balance with the atmosphere. If we want them to keep helping us, we need to create conditions where they can thrive.”

✍ Conclusion: A Wake-Up Call from the Canopy

The rainforests of Queensland are sounding an ecological alarm. For the first time, a pristine tropical forest has flipped from carbon sink to source — not because of logging or land clearing, but because of climate change alone.

This isn't just an Australian issue. It’s a preview of what might happen across the globe if we don’t act swiftly and decisively. Forests are among our most powerful allies in the fight against climate change — but even they have limits.

Protecting and restoring rainforests, rethinking emissions targets, and acknowledging the hidden feedback loops of climate change are now more urgent than ever. Nature is giving us clear signals. Whether we listen is up to us.

Thank you !