article image source: theconversation.com (Link)

2-Million-Year-Old Teeth Reveal Secrets from the Dawn of Humanity: Ancient Proteins and Enamel Pits Rewrite Human Evolution

2-million-year-old pitted teeth from our ancient relatives reveal secrets about human evolution

image source: theconversation.com

• Ancient tooth proteins from Paranthropus robustus reveal unexpected genetic diversity.

• Mysterious enamel pits may be inherited traits, not signs of disease.

• New molecular and dental evidence reshapes the early human family tree.

advertisement

The story of human evolution is increasingly being written not only in bones, but in teeth.

Recent discoveries involving 2-million-year-old fossil teeth from southern and eastern Africa are transforming what we know about early hominins, especially Paranthropus robustus, a powerful, large-jawed relative of early humans.

Through cutting-edge ancient protein analysis and the study of unusual enamel pitting, scientists are uncovering genetic diversity, evolutionary relationships, and developmental traits that challenge long-held assumptions about our ancient family tree.

For nearly a century, Paranthropus robustus has fascinated researchers.

First discovered in 1938 in South Africa, this upright-walking hominin lived between about 2.25 and 1.7 million years ago.

It had massive jaws, thick enamel, and large teeth suited for chewing tough vegetation.

Its fossils are part of a remarkable record that also includes species such as Australopithecus africanus, Australopithecus sediba, Homo habilis, Homo erectus, and ultimately Homo sapiens, which emerged in Africa around 300,000 years ago (with evidence of early presence in South Africa around 153,000 years ago).

For decades, scientists debated whether differences in P. robustus fossils reflected sexual dimorphism (male vs. female differences) or whether they pointed to multiple species.

Ancient DNA could not survive Africa’s warm climate, leaving these questions unresolved.

To overcome this, researchers turned to paleoproteomics — the study of ancient proteins — extracting preserved enamel proteins from four fossil teeth found at Swartkrans Cave in South Africa’s Cradle of Humankind.

Because proteins bind tightly to enamel and bone, they can survive for millions of years, far longer than DNA.

The results were groundbreaking.

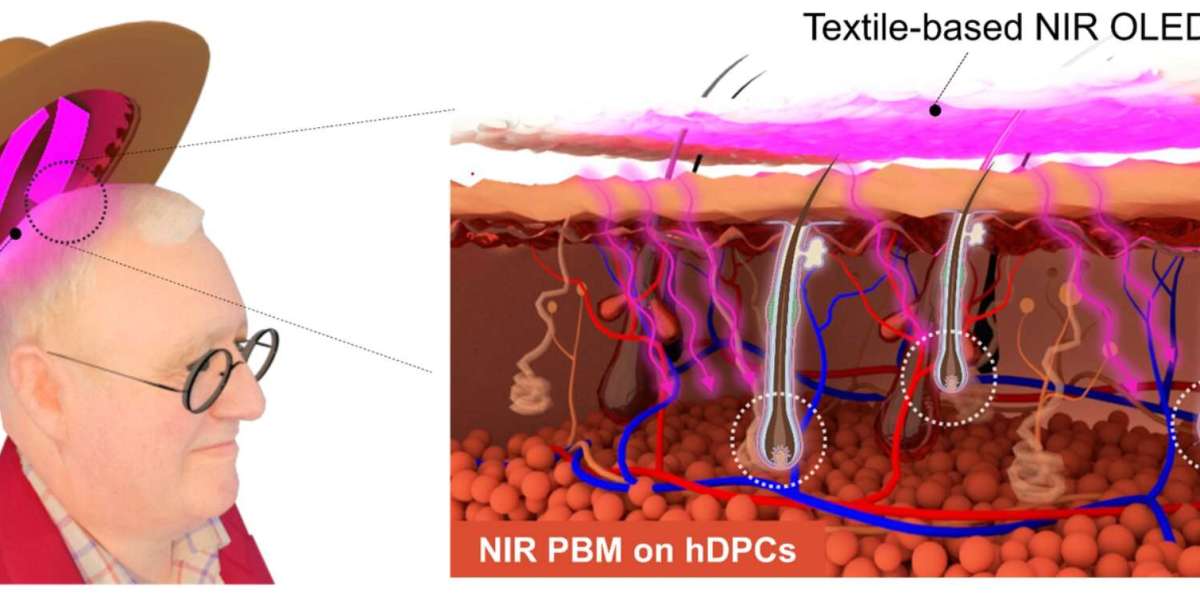

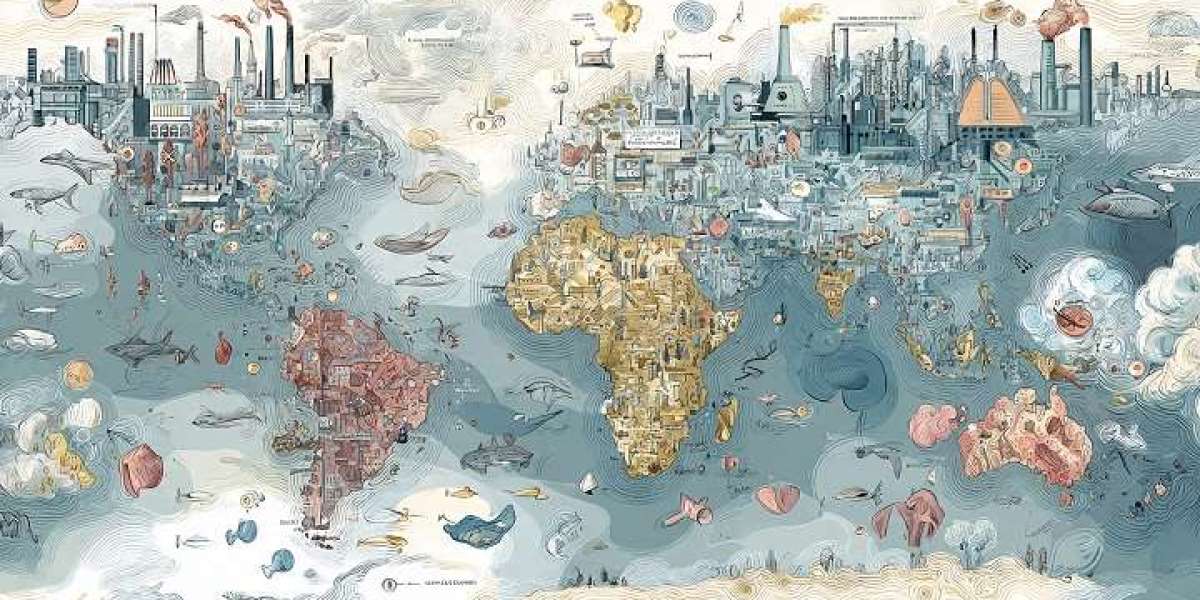

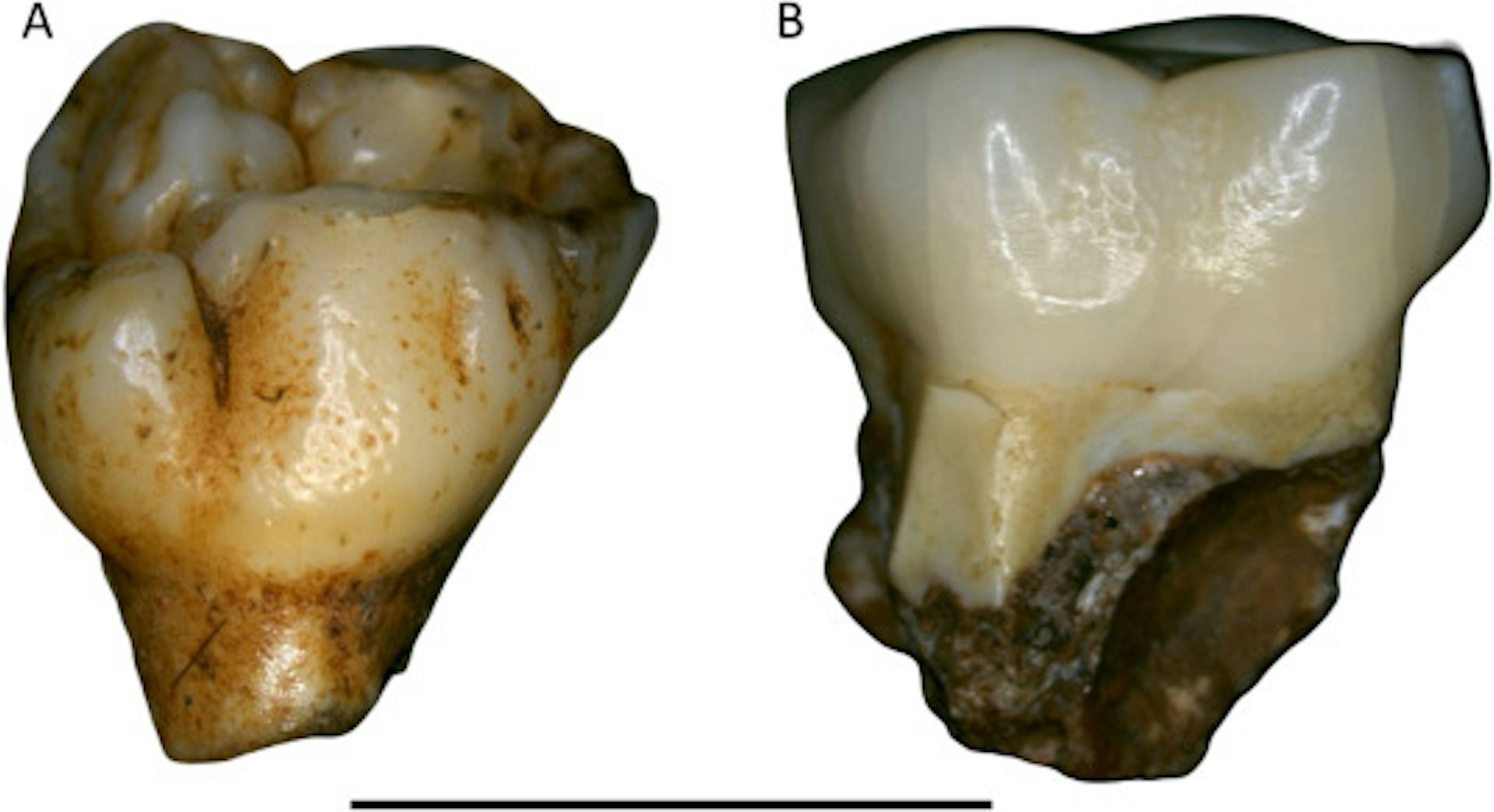

Uniform, circular and shallow pitting on teeth may be a previously undetected clue about evolutionary relationships.

image source: Towle et al. / Journal of Human Evolution sciencedirect.com

Protein analysis identified the biological sex of the individuals — two male and two female — providing rare molecular insight into fossils nearly 2 million years old.

Even more striking were subtle differences in the enamel protein called enamelin.

Two fossils shared an amino acid sequence also found in modern humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas.

The others had a version unique so far to Paranthropus.

One individual carried both variants — the first documented case of heterozygosity (two gene versions) detected in proteins this ancient.

According to researchers, this suggests that P. robustus may not have been a single uniform species, but rather a genetically diverse population or possibly multiple closely related lineages.

While proteins revealed hidden genetic variation, another study focused on something more visible — tiny, shallow pits in tooth enamel.

These uniform, circular depressions were first noted in Paranthropus robustus but were long assumed to be defects caused by childhood stress, malnutrition, or disease.

However, new research published in the Journal of Human Evolution challenges that assumption.

advertisement

Scientists examined fossil teeth from the Omo Valley in Ethiopia — a region preserving over 2 million years of hominin evolution — along with material from South African sites such as Drimolen, Swartkrans, and Kromdraai.

They found that this consistent pitting appears frequently in both eastern and southern African Paranthropus, and also in some early eastern African Australopithecus dating back about 3 million years.

Notably, it is absent in southern African Australopithecus africanus and in the genus Homo.

The pits are uniform in shape and size, subtly spaced, and often clustered on specific parts of the tooth crown.

They do not resemble stress-related enamel defects, which usually form horizontal bands affecting multiple teeth developing at the same time.

Instead, researchers argue the pitting likely has a developmental and genetic origin — possibly a byproduct of changes in enamel formation.

Although a rare modern condition called amelogenesis imperfecta affects enamel in about one in 1,000 people today, the fossil pitting appears in up to half of Paranthropus individuals, suggesting it was not a harmful disorder but a stable inherited trait.

If confirmed as genetic, this enamel pitting could become a powerful evolutionary marker.

It may support the idea that Paranthropus forms a monophyletic group — species descending from a recent common ancestor — rather than evolving independently from different Australopithecus species.

Intriguingly, similar pitting may appear in fossils of Homo floresiensis, the so-called “hobbit” species from Indonesia, though researchers caution that more study is needed before drawing conclusions.

Taken together, the protein data and enamel morphology paint a more complex picture of early human evolution.

Rather than a simple branching tree, our ancestry may resemble a braided stream of overlapping populations, genetic variation, and developmental experimentation.

By combining molecular evidence with traditional fossil anatomy, scientists are developing a new blueprint for studying human origins — one that is increasingly precise, inclusive of African research leadership, and capable of revealing biological details once thought forever lost.

advertisement

Conclusion

Two-million-year-old teeth are no longer silent relics.

They are molecular archives preserving sex, genetic diversity, and developmental traits from the dawn of humanity.

Ancient proteins from Paranthropus robustus reveal that early hominins were more genetically varied than previously assumed, while enigmatic enamel pits suggest inherited traits that may redefine evolutionary relationships.

Together, these discoveries remind us that human evolution was not a straight line but a dynamic, branching, and sometimes converging journey.

With advancing paleoproteomic techniques and renewed focus on Africa’s fossil heritage, the next revelations about our origins may already be waiting inside the enamel of a single ancient tooth.

Key Points

Ancient enamel proteins identified sex and genetic variation in Paranthropus robustus.

Uniform enamel pits may be inherited evolutionary traits rather than disease markers.

Combined molecular and dental evidence suggests a more complex early human family tree.

advertisement

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why are 2-million-year-old teeth so important for studying human evolution?

Teeth preserve extremely well over time. Their enamel can protect ancient proteins for millions of years, providing molecular data even when DNA is no longer preserved.

2. What did scientists discover about Paranthropus robustus?

Protein analysis revealed biological sex and unexpected genetic diversity, suggesting the species may have been more complex than previously believed.

3. What are the mysterious enamel pits?

They are small, uniform, circular depressions in tooth enamel that likely have a genetic and developmental origin rather than being caused by disease or malnutrition.

4. Do modern humans have this enamel pitting?

No. The uniform pitting described in these fossils has not been found in the genus Homo, except in rare pathological cases.

5. How does this change our understanding of the human family tree?

It suggests early hominins may have been more genetically diverse and evolutionarily interconnected than previously thought.

Sources

- ScienceDaily – Report on ancient protein analysis of Paranthropus robustus teeth

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/11/251101000412.htm - The Conversation – Study on 2-million-year-old enamel pitting and evolutionary significance

https://theconversation.com/2-million-year-old-pitted-teeth-from-our-ancient-relatives-reveal-secrets-about-human-evolution-258390

Thank you !