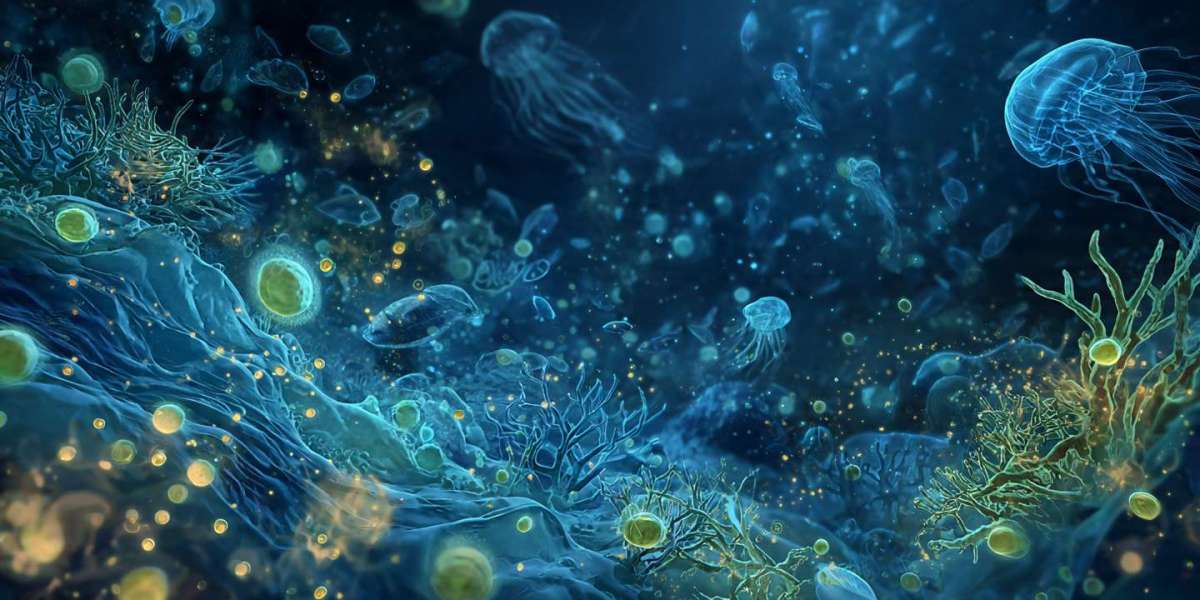

In the heart of dense corn fields, where plants crowd and compete for light and food, a new study has revealed an unexpected secret: plants communicate with each other through aromatic scents, reshaping the soil around them to strengthen their resistance to pests, even at the expense of their own growth.

In the study, published August 14 in the journal Science, an international research team highlighted an aromatic compound called linalool, which is constantly emitted from corn leaves and plays a pivotal role in a "collective alarm network" among plants.

Plants Talk, Soil Responds

Lead author of the study, Ling-Fei Hu, a professor of botany at Zhejiang University in China, explained that planting crops at high density is usually associated with increased productivity, but it also has a more dangerous side: it provides an ideal environment for insect reproduction and the spread of diseases.

He adds, "While scientists have been studying for decades how plants change their shape and roots to adapt to these conditions, the question remains: How do these plants manage their immune systems in such crowded conditions?"

Hu explains that the answer came from corn. "We observed that plants in the inner rows of dense fields are less susceptible to insect attacks than their counterparts at the edges, but at the same time, they grow more slowly."

He adds that laboratory experiments have demonstrated why soil previously planted with dense plants retains an "environmental memory" effect that reduces new plant growth but enhances their resistance to worms, viruses, and fungi.

advertisement

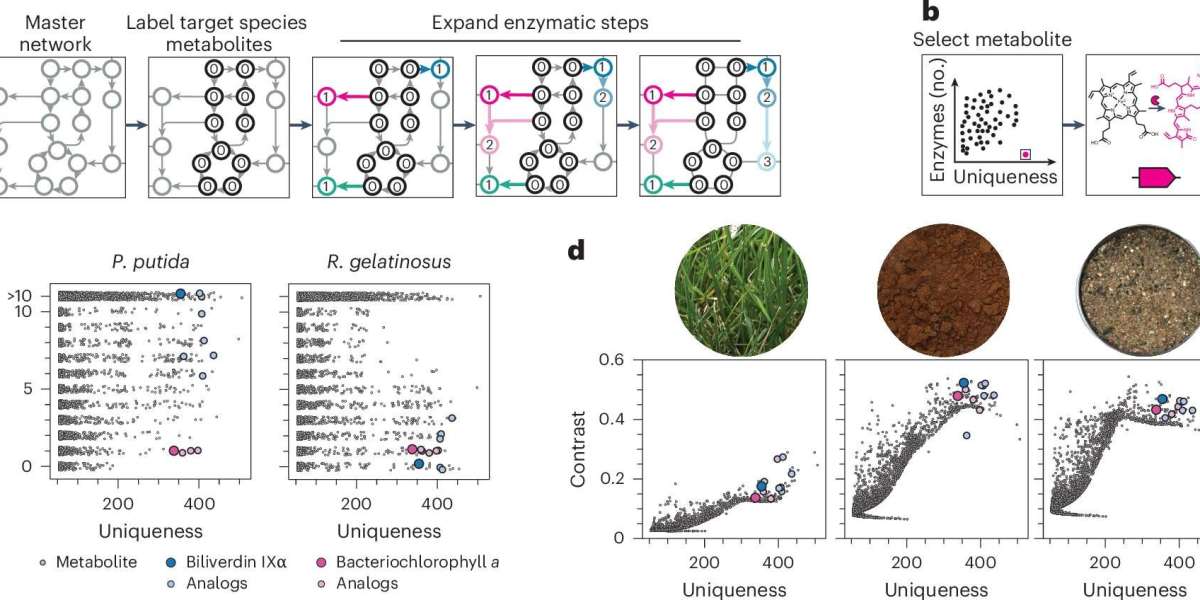

By analyzing the gases emitted by plants, the scientists identified linalool as the first signal in this complex chain. When its scent accumulates in crowded fields, neighboring plants pick it up, activating hormonal signals in the roots known as "jasmonate signals." These, in turn, stimulate the plant to secrete specific defensive compounds from the roots known as benzoxazenoids.

What happens next is astonishing: these compounds alter the composition of soil microbes, encouraging the growth of bacteria that reduce plant growth but increase its resistance. The result is that subsequent generations of plants grown in these soils find themselves better prepared to deal with threats, even before pests attack them.

A potential revolution in sustainable agriculture

The lead author of the study emphasizes that this discovery reaffirms the "difficult equation" facing plants: investing in growth or defense? Under normal conditions, plants develop balanced strategies between the two. But in dense fields, the study indicates that corn tends to favor defense, even if it results in reduced biomass and grain size.

"We were surprised by the speed of this response. After just three days of planting in crowded conditions, we observed that the soil began to transmit a clear effect to the new plants: slower growth but greater resistance to insects and viruses. It's a clever mechanism, similar to a collective chemical alarm network," the researcher said.

These findings open the door to new ideas in plant breeding and crop management. If plants can be enhanced to produce or respond to a compound like linalool, farmers could in the future partially eliminate the need for chemical pesticides and rely on a "natural immunity" activated by the plants themselves.

Hu notes, "Imagine if, through hybridization or bioengineering, we could produce high-yielding varieties capable of emitting these defense signals when needed. That would be a step toward more environmentally friendly agriculture and less reliance on pesticides."

Thank you !