article image source: phys.org (link)

When it comes to learning life’s first lessons, family matters — but not always in the way we expect. A new study has revealed that for young songbirds, siblings may be the true mentors, playing a far greater role in shaping behavior and survival skills than parents do.

advertisement

A New Look at Learning Beyond Parental Care

Researchers from the University of California, Davis, and the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior have discovered that juvenile great tits (Parus major) rely heavily on their brothers, sisters, and nearby adults to learn essential survival skills. The findings, published in PLOS Biology, offer a fresh understanding of how animals acquire knowledge when parental guidance is brief.

“In most species, we assume parents are the primary teachers,” explained lead author Sonja Wild. “But what happens when parents step back early and offspring must learn on their own?”

The great tit provided the perfect model to explore that question. These small songbirds receive only about ten days of parental care after leaving the nest — just enough to get started, but far from enough to master independence. After that, parents stop feeding them, and the fledglings must quickly figure out how to find food, avoid predators, and navigate their social world.

Juvenile great tits learn to solve foraging puzzles

Testing Bird Brains with Puzzles

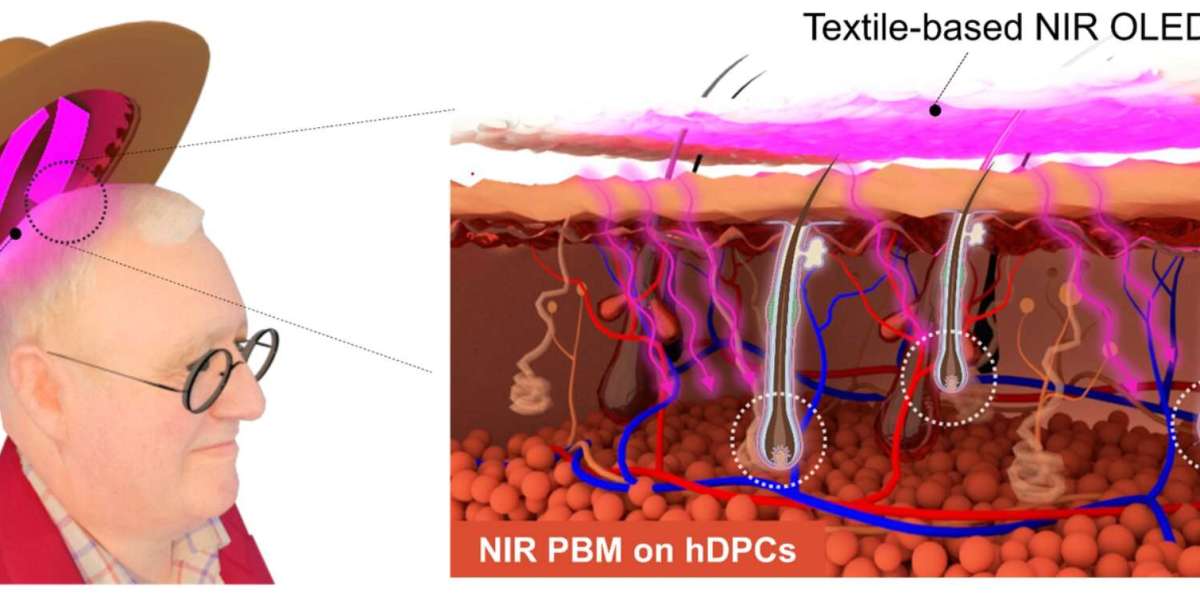

To track how young birds learn, the researchers followed 51 breeding pairs and 229 fledglings for ten weeks in the wild. They set up automated “puzzle boxes” containing mealworms, which could be accessed by sliding a small door left or right. Each bird carried a tiny microchip, allowing scientists to record every visit, success, and failed attempt — tens of thousands of data points in total.

This detailed setup revealed a fascinating pattern. While juveniles were more likely to engage with puzzles if their parents were skilled at solving them, their actual methods came from others. The first birds in each sibling group tended to copy unrelated adults three times more often than they copied parents. Once one fledgling learned how to open the box, the rest of its siblings followed suit — about 94% of later learners adopted the same technique as their sibling.

In other words, parents sparked curiosity, but siblings provided the real instruction.

A European great tit flies off with a mealworm after solving a sliding door foraging puzzle.

(Sonja Wild, UC Davis) - image source: caes.ucdavis.edu

Why Siblings Matter So Much

The study suggests that proximity and timing play key roles. After fledging, brothers and sisters often travel and forage together, forming tight-knit groups. When one bird discovers an effective feeding strategy, the others quickly imitate it. Copying a successful sibling is faster, safer, and more efficient than trial-and-error learning — a major advantage when energy and time are scarce.

This dynamic also helps explain why related birds within the same family often display similar behaviors, even when parental involvement is minimal. The cultural “signature” of a family, it seems, can be passed from chick to chick, not just from parent to child.

A Broader Social Network

Beyond sibling influence, the research highlights the importance of wider social learning. Many of the first problem-solvers were not parents but experienced neighboring adults. These birds acted as initial role models whose behaviors spread through sibling groups, creating a cascade of knowledge across the community.

Such findings align with growing evidence that animal societies rely on complex networks of shared information. Learning, in this context, is not a linear handoff from parent to offspring but a rich exchange within a social web.

Lessons for Conservation and Resilience

Understanding how animals learn has major implications for conservation. When species can draw knowledge from multiple sources — siblings, peers, and neighbors — they become more adaptable to environmental change.

“The more diverse the cultural routes, the more robust a population can be,” said Wild. “Multiple role models reduce reliance on any single source.”

For conservationists, these insights point to practical strategies. Protecting habitats where young birds can remain with siblings or join mixed-age foraging groups could help maintain cultural transmission in the wild. It might also make populations more resilient in the face of habitat loss or climate change.

A Family Lesson Beyond the Nest

While this research focuses on birds, its message resonates more broadly. Learning, cooperation, and adaptation thrive when knowledge is shared — not just handed down. Whether in birds or humans, siblings and peers often become our most influential teachers, guiding us through the early trials of independence.

The study reminds us that even in nature’s smallest families, wisdom flows in many directions. Parents may open the door, but it’s the brothers, sisters, and neighbors who often show how to fly through it.

Sources

Thank you !