article image source: livescience.com (link)

Long before sunglasses became a mark of glamour, rebellion, or style, they were tools of pure survival. What began as a clever response to blinding Arctic light thousands of years ago evolved into one of the world’s most iconic fashion accessories — merging protection, science, and art through centuries of innovation.

advertisement

When the Sun Was the Enemy: The Inuit Invention

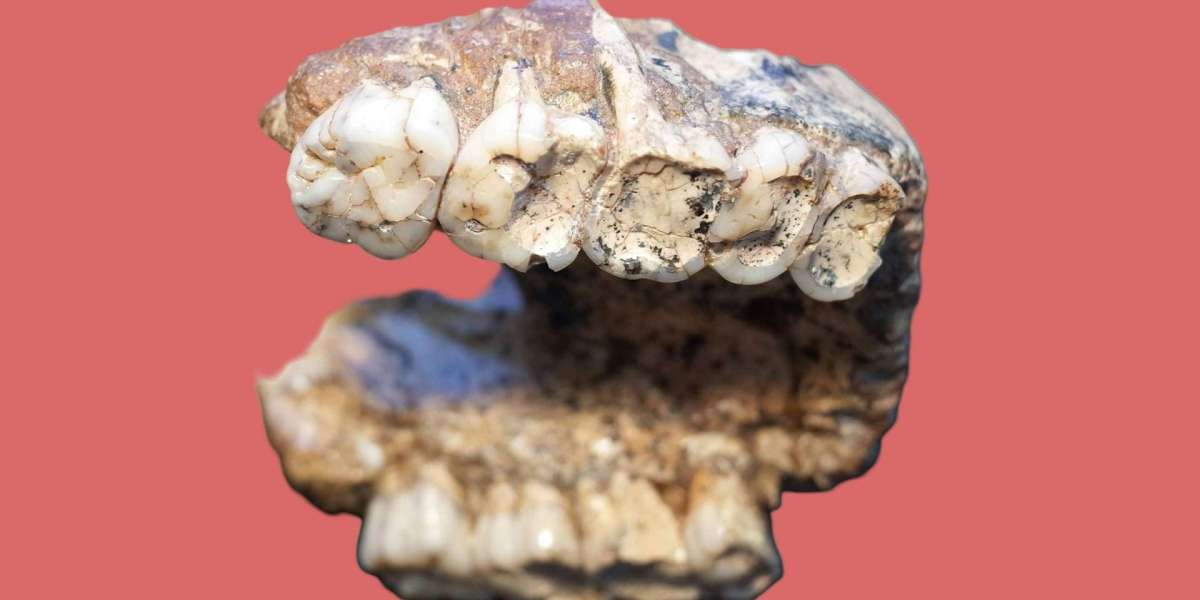

In the frozen landscapes of the Arctic, the Inuit people faced an invisible but powerful threat: snow blindness — a painful burn of the eyes caused by intense sunlight reflecting off ice and snow. Modern explorers rely on UV-blocking goggles, but the Inuit devised their own ingenious solution long before science understood ultraviolet radiation.

They carved protective eyewear from bone, wood, or ivory, shaping narrow horizontal slits that let in just enough light to see while blocking glare. Some even blackened the inside of their goggles with soot to absorb stray light. These early designs, discovered across Alaska, Siberia, and Canada, were the world’s first true sunglasses — combining necessity, craftsmanship, and optical physics centuries before lenses were invented.

This remarkable innovation wasn’t just practical; it was deeply cultural. Many goggles bore intricate patterns or regional designs, reflecting both artistic identity and adaptation to local conditions. The Inuit achievement remains one of humanity’s earliest examples of technology born directly from environmental need.

image source: conexiant.com

The East Looks Through Smoky Quartz

Far from the Arctic, 12th-century China saw another breakthrough. Chinese artisans crafted flat panels of smoky quartz, known as “smoke-colored glasses.” These were not for protection against UV rays but served a different purpose — judges wore them in court to conceal their emotions and maintain impartiality.

These early “dark glasses” introduced a new idea: eyewear could hide as well as protect, foreshadowing the mystique that sunglasses would later embody in modern culture.

From the Roman Empire to the Renaissance

Even the ancient Romans toyed with the concept. Emperor Nero was said to watch gladiator games through polished emeralds to soften the sun’s glare. While historians debate the accuracy of that tale, it illustrates humanity’s enduring fascination with taming light.

By the 17th century, a major leap occurred in Venice, home of Europe’s most advanced glassmakers. Venetian artisans began producing tinted glass lenses — sometimes multifaceted and decorative — known later as “Goldoni glasses.” Initially used by sailors and the elite to reduce glare off the sea, they were among the first true glass-based sunglasses.

Science Joins the Story: The 18th and 19th Centuries

In 1752, English optician James Ayscough experimented with blue and green tints in eyeglasses, believing they could correct vision and relieve eye strain. Though his aim wasn’t sun protection, Ayscough’s experiments bridged the gap between corrective lenses and light filtering, setting the stage for modern sunglass science.

By the 1800s, tinted glasses were prescribed for ailments like headaches or light sensitivity, and even recommended to syphilis patients. Across Europe and America, “green spectacles” gained popularity among intellectuals like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, who saw them as both practical and refined.

Interestingly, the term “sunglasses” in its modern sense didn’t appear in English until 1817 — a full millennium after the Inuit’s first goggles.

image source: allaboutvision.com

The Modern Revolution: From Utility to Fashion

The industrial 20th century transformed sunglasses from medical tools into mass-market must-haves.

In 1929, American entrepreneur Sam Foster introduced affordable, mass-produced celluloid sunglasses under the Foster Grant brand, selling them to beachgoers in Atlantic City. Just a few years later, Edwin Land of the Polaroid Corporation invented polarized lenses, revolutionizing glare protection for drivers, athletes, and pilots.

Meanwhile, Hollywood gave sunglasses their star power. Silent-film actors began wearing them on set to protect against harsh studio lights — and soon, everywhere else. By the 1930s, film icons and military heroes alike, from General Douglas MacArthur to Audrey Hepburn, made sunglasses synonymous with coolness, confidence, and mystery.

A Fusion of Fashion, Function, and Science

The 20th century saw sunglasses evolve into an everyday necessity. Styles like the aviator, cat-eye, and wayfarer defined decades of pop culture. Behind the aesthetics, science continued to advance: UV-blocking coatings, anti-glare polarization, and scratch-resistant lenses turned sunglasses into serious protective gear.

Today, experts like the American Optometric Association emphasize that wearing sunglasses year-round helps prevent cataracts, macular degeneration, and skin cancer around the eyes. It’s not just about looking good — it’s about keeping your vision safe.

From Ancient Innovation to Timeless Symbol

It’s remarkable to think that a piece of carved ivory worn by Inuit hunters thousands of years ago paved the way for the sleek designer shades we wear today. Across cultures and centuries, humans have turned necessity into artistry — transforming a practical tool for survival into a symbol of independence, intelligence, and self-expression.

When you slip on a pair of sunglasses, you’re not just blocking glare — you’re wearing the story of human adaptation, creativity, and resilience. From the frozen tundra to the city streets, the same instinct remains: to face the light, and still see clearly.

Sources

The New Optometrist – “The Ancient Origins of Sunglasses” (Conexiant.com)

Perrysburg Eye Center – “Sunglasses: Protective Eyewear’s Surprising Origin”

Olivio & Co – “When Were Sunglasses First Invented? Exploring Their Origins”

Thank you !