article image source: earthlife.net (link)

Birds of paradise, members of the Paradisaeidae family within the order Passeriformes, are primarily found in eastern Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and parts of eastern Australia. This family encompasses 45 species spread across 17 genera, with the majority of these species inhabiting dense rainforests. Known for their elaborate and striking plumage, especially in males, these birds have captured the fascination of naturalists and birdwatchers alike. Their males often display extravagant feather extensions from the beak, wings, tail, or head, and they exhibit sexual dimorphism, meaning males and females look quite different.

Most birds of paradise are fruit eaters, although some species also consume arthropods. The family displays diverse mating behaviors, ranging from monogamy to lek-based polygamy, with elaborate courtship rituals that often include dancing, singing, and feather displays.

Taxonomy and Evolution

The family Paradisaeidae was first introduced by English naturalist William Swainson in 1825, with Paradisaea as the type genus. For many years, birds of paradise were thought to be closely related to bowerbirds, but recent studies have shown they share a more distant relationship with this group. Instead, they are most closely related to the crow and jay family (Corvidae), monarch flycatchers (Monarchidae), and Australian mudnesters (Struthideidae).

Molecular studies conducted in 2009 suggested that birds of paradise emerged about 24 million years ago, with further analysis revealing five major evolutionary clades within the family. These clades represent the distinct evolutionary lines within this diverse group, with one clade containing the monogamous manucodes and the paradise-crow, and another containing the sicklebills and riflebirds. The family has also undergone some taxonomic reclassification, as several species once linked to birds of paradise, like satinbirds and the Macgregor’s bird-of-paradise, have been reclassified into separate families.

Physical Characteristics

Birds of paradise vary in size from the small king bird-of-paradise at 50 grams and 15 cm long, to the large black sicklebill, which can reach up to 110 cm in length. Males typically have longer, more elaborate tails than females, with some species exhibiting extreme size differences. The males of many species also sport specialized feathers and features to enhance their courtship displays. The bill shape varies significantly across species, from long, decurved bills to shorter, more slender ones.

Raggiana bird-of-paradise (Paradisaea raggiana) - source: wikipedia.org

Plumage and Sexual Dimorphism

The males of most species are known for their colorful and extravagant plumage, which they use in courtship displays. This plumage variation is often linked to the species' breeding system. For instance, the socially monogamous manucodes have relatively simple plumage, while sexually dimorphic species, such as those in the Paradisaea genus, feature brightly colored males and more muted, camouflaged females. Interestingly, juvenile males initially have plumage resembling females, which provides protection from predators until they mature.

advertisement

Habitat and Behavior

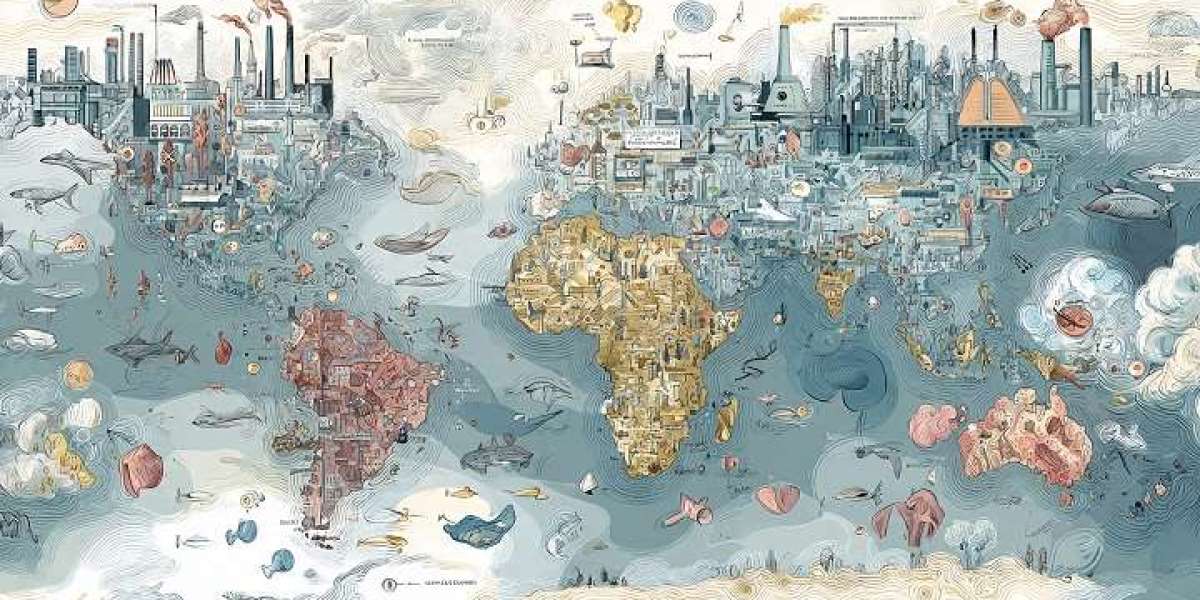

Birds of paradise primarily occupy tropical rainforests, although some species are found in coastal mangroves or sub-tropical wet forests. The island of New Guinea is the epicenter of bird-of-paradise diversity, with most species residing there. Some species are also found in eastern Australia and the Maluku Islands. Many birds of paradise are solitary, with species that feed on fruit often spending time in the forest canopy, while insect-eating species tend to remain in lower, more territorial areas.

Their diet is heavily frugivorous, although many species also consume insects. They play an important role in seed dispersal due to their frugivorous habits. Despite their social tendencies while feeding, these birds are generally territorial and spend much of their lives alone.

Mating and Courtship

The courtship behaviors of birds of paradise are famously elaborate. Males engage in complex rituals to attract females, which can include dancing, vocalizations, and displaying their colorful plumage. The most striking courtship displays are seen in species with a lek-based mating system, where males congregate in a specific area and perform their displays for the attention of females. Female preference is a key driver of the evolution of the males' spectacular ornamental features, including their feathers, colors, and behavior.

Reproduction

Birds of paradise build their nests using soft materials such as leaves, ferns, and vine tendrils. The number of eggs varies by species, but many larger birds of paradise lay just one egg per clutch, while smaller species may lay 2–3 eggs. After a 16-22 day incubation period, the young fledge and leave the nest between 16 and 30 days of age.

Conservation Status

The stunning plumes of birds of paradise have long been sought after, both for ceremonial use and as adornments in fashion. This has led to hunting pressures, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Deforestation and habitat destruction continue to pose significant threats to many species, leading to the endangered status of several birds of paradise. However, legal protection and sustainable hunting practices are now in place to safeguard their populations.

Birdwatching and Cultural Significance

In recent years, birdwatching tours in Papua New Guinea and surrounding regions have gained popularity, as birdwatchers flock to observe various species in their natural habitat. This surge in interest has contributed to a decline in the local hunting of birds of paradise. Indigenous communities have long used the birds' plumes in their rituals, and these plumes were also highly valued in Europe during the 19th century.

Today, the beauty and rarity of birds of paradise continue to captivate naturalists, and they remain symbols of both biodiversity and the need for conservation efforts in tropical ecosystems.

Thank you !